For those of us fueling ourselves with the late-night pizza and discount wine that a graduate stipend affords us, the idea of spending at least a year or two on poverty-level incomes may not feel shocking. It may, however, be more common than we once thought.

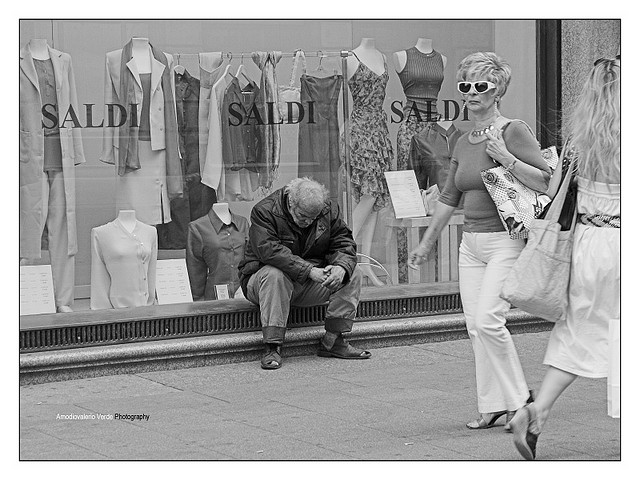

A new study by sociologists Thomas Hirschl and Mark Rank finds that nearly 60% of Americans will spend at least one year living off of poverty-level incomes. These rates are heavily concentrated among those under the age of 30, with 42% of those young adults experiencing at least one year of poverty (20th percentile of income), and 23% experiencing extreme poverty (10th percentile of income). And for those without savings or parental help to fall back on, these low incomes can lead to homelessness and long-term financial struggle. According to their findings, 12% of Americans spend nearly a decade or more in poverty.

“There’s a great deal of fluidity in the income distribution,” Hirschl told Pacific Standard Magazine. “Economic insecurity—this is not a small effect. We have a tough road ahead of us.”