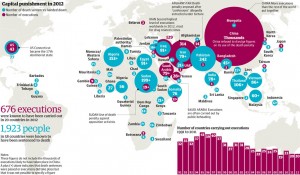

In societies that allow for the death penalty in criminal punishment, there has been a shift toward ever more “humane” methods of execution. The rhetoric surrounding these changes generally involves not violating the rights of the prisoner by applying a cruel or unusual punishment—that is, just death, not torture.

In an interview with The Voice of Russia, University of Colorado professor Michael Radelet explains that the real motivations for a turn toward the medicalized execution may have more to do with minimizing the suffering of the audience than the condemned. When asked if there was a humane way to kill someone, Radelet points out that shooting and guillotining have no history of failure, unlike generally bloodless lethal injection (recently pegged at 7% in the U.S. by Amherst College’s Austin D. Sarat).

“Most state authorities in the US couldn’t care less whether or not the inmate suffers, what they care about is the suffering by the audience. This all has to do with the spectators.” Apparently, modern sorts want their vengeance deadly, but not grisly.

Radelet says that the death penalty is mainly political, allowing the public to be convinced their society is tough on crime. If the obvious question in the death penalty debate is: Do you support the death penalty? Data Radelet cites points to a more thorough question: Do you support the death penalty, given the alternative of life without parole? When the question is rephrased, support for the death penalty actually goes up a bit. It seems that, when the respondents consider a lifetime of suffering against death, their views on the suffering of others shift yet again.