Over the last year, bystanders have recorded numerous instances of confrontation between police and black students, from one officer pointing his gun at an unarmed black youth during a pool party in Texas to another officer flipping over a black girl still seated in her desk in a South Carolina high school. Media reports often blame black girls for defying authority figures while excusing the behaviors of school officials and law enforcement officers. Recent reports including Kimberlé Crenshaw’s, “Black Girls Matter: Pushed Out, Overpoliced and Underprotected,” contextualizes the serious effects of harsh punishment as black girls disproportionately enter the school-to-prison pipeline.

Over the last year, bystanders have recorded numerous instances of confrontation between police and black students, from one officer pointing his gun at an unarmed black youth during a pool party in Texas to another officer flipping over a black girl still seated in her desk in a South Carolina high school. Media reports often blame black girls for defying authority figures while excusing the behaviors of school officials and law enforcement officers. Recent reports including Kimberlé Crenshaw’s, “Black Girls Matter: Pushed Out, Overpoliced and Underprotected,” contextualizes the serious effects of harsh punishment as black girls disproportionately enter the school-to-prison pipeline.

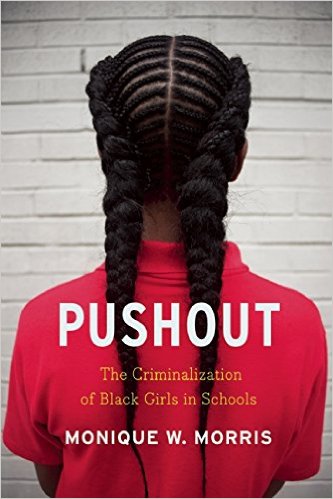

Monique Morris sheds additional light on the topic in her new book, “Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools.” Morris interviewed several young black girls in group homes, foster care, and juvenile detention centers in cities including Chicago, San Francisco, New York, and Boston. She discovered that several girls experienced various forms of physical and sexual violence. Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow, praised the book, calling it “A powerful indictment of the cultural beliefs, policies, and practices that criminalize and dehumanize Black girls in America,” while activist Gloria Steinhem wrote that Morris “tells us exactly how schools are crushing the spirit and talent that this country needs.”