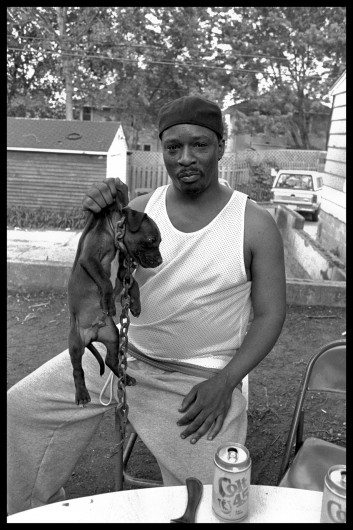

This is little Geno. I’m big Geno. He’s going to be a security dog. I’m going to take my time with him. I’m just trying to get his neck to be strong. The chain is to put muscles in his chest. Right now he’s young. As he gets old he’ll get used to it…Once he sees me with it, he know he’s got to put it on. At first he didn’t want to have it on, but now he’s used to it. It’s not being abusive. You can train a dog how you want to train a dog, just like a child… You know, you just raise your dog just the way you want to be raised up. That’s all that is.

Wing Young Huie: When photographing, I try to present people as they present themselves, but a photograph is just a snippet of that person. If you took a thousand photographs of someone, which photograph would be truest? And who decides the truth about any photograph—the person in it, the person who took it, or the person looking at it?

This is to say, you never know how a photograph will be interpreted. I have photographs that seem innocuous to me but instill fear in others. This photograph of a man and his dog, in particular, often gets a visceral reaction. Recently, I was putting up a permanent installation in a public building of about 50 photographs from my Lake Street USA series. To decide which photo should go where, I laid them all out along the wall.

Perhaps because of the scandal concerning Michal Vick, still fresh in the public’s consciousness, or perhaps because I’ve become more cautious in which images I deem proper for public settings, I told the woman helping me hang photos that this one might cause trouble. Sure enough, a few moments later an African American man walked by and blurted, “This is really offensive to me! This only perpetuates what people already think of us.” We ended up putting the photograph in a basement room.

Doug Hartmann: When I first saw this image, I wasn’t particularly moved to comment—not because I didn’t think it was interesting, but because I thought there was much more sociological meaning and significance in this picture than first meets the eye. I was pretty sure the sociological dimensions were more complicated, controversial, and awkward than I wanted to delve into. However, when I learned that the piece had indeed proven controversial for Wing, I decided to weigh in.

Most of what I knew and thought about this piece came through the lens of my knowledge and understanding of the arrest and conviction of famed NFL quarterback Michael Vick for being involved with the breeding, beating, and brutal training of pit bulls for underground dog-fighting. Indeed, over the past few years I have read or heard a surprising number of papers and presentations on Vick, and at least two things stand out.

One has to do with how the whole incident played off of and reinforced some of our worst racial prejudices about African American men (athletes in particular). To give just one example, I recently read a paper that compared media coverage of the initial allegations against Vick with those against Ben Rothlesberger, a white NFL player who was accused (though ultimately did not stand trial) for rather extreme sexual harassment charges. Although Rothlesberger’s charges were arguably more egregious than Vick’s, the media coverage of the accusations against Vick was far more extensive and negative, playing up the fears and threats a famous black man represented in the culture. No one could dispute his crimes were disturbing; but what was more problematic was how this incident functioned to reinforce a whole bunch of stereotypes about the crime and violence in the black community. My sense is these stereotypes were what made folks in the community so uncomfortable with the original public placement of Wing’s photograph.

We often hear there’s “some truth in every stereotype”—and this, what’s assumed and then reinforced about a subculture of crime and violence in the black community, is the second thing about the Vick case that really stood out to me. It made me awkward and uncomfortable—not just the animal cruelty itself, but the larger context of violence and illegality in which these behaviors were normalized. In this context, I was particularly interested to read Big Geno’s comments to Wing, especially his parallel between training dogs and raising kids. I’m pretty sure I don’t agree, but I am intrigued by the view and the otherwise unfamiliar life-world that produces it

Many of these issues came to a head in a submission on animals and society we worked with for Contexts a little while back. That piece, “Our Animals, Ourselves,” was largely about the close, reciprocal relationships between animals and the humans who own, identify, and associated with them. In its first iteration, the version of the article we sent out for peer review, there was a passage about the racialization of pit bills because of their close association with young African American men in contemporary U.S. culture. Without a doubt, this passage proved one of the most volatile and contested of any we had to adjudicate during our editorial tenure. Some readers loved the point and believed it to be grounded and insightful with many historical parallels; others hated it as overblown and unfounded. We never knew quite what to make of these differences and ultimately “punted”—that is, we took out the most specific, racially sensitive material and ran a watered down version of the point. “Pit bulls—and more importantly, their owners—have become scary and frightening monsters to many Americans. No stereotypical portrayal of an African American, Latino, or working-class skinhead gang is complete without a pit bull in the picture. So pit bulls… are defined as dangerous, hated by association, and given no place in civilized society.”

Looking back, I still don’t know if we handled that article correctly—the final article wasn’t nearly as explicit or provocative about the racial dimensions as the original. But both the experience of editing the piece and choosing what to run highlight, I think, the controversy and volatility contained even a seemingly straightforward image: a man and his dog become, instead, a place where race, stereotypes, and animals all come together.

Comments 6

Kyle Green — March 22, 2012

This is a very provocative photo and commentary.

Looking up the photo and Big Geno's comments reminds me how different people's understanding of the purpose of having a dog/pet can be.

Last spring TSP covered a nytimes article that discussed how these different understandings of the role of the pet can lead to very emotional reactions and also tends to follow class divides.

(http://thesocietypages.org/citings/2011/03/15/canines-and-class-conflict/)

Geno's commentary provided me with an important reminder that too often we make assumptions that if someone has a different understanding of how to raise a dog and why they have a dog, it means the emotional connection is absent. That is clearly wrong here (the dog even shares Geno's name). This is a difficult lesson to hold onto when confronted with more extreme cases, like dog fighting rings, but still a valuable one.

syed ali — March 22, 2012

another thing about the vick case, though, was that americans love their dogs, often more than they love other people, which i think partially might explain the visceral, pretty much universal outrage. so the comparison with rothlesberger isn't quite so direct. dogs are pure and innocent and need to be protected, while women in such cases even today, there's always *that* question in the courts and the press. note too that black athletes also get passes, legal and media-wise, similar to rothlesberger.

Sarah Shannon — March 26, 2012

This is interesting to read and I'm of two minds about the photo. As a sociologist, I can agree and nod along with much of this analysis. But as a resident of a neighborhood in Minneapolis with a high density of pit bulls (North Minneapolis), I've seen all too personally the negative impacts that mistreatment of these animals can have on a community. Ask me sometime about my pit bull stories - these include calls to animal control, police with guns drawn on pit bulls on busy streets (with toddlers near the line of fire), and dogs shot dead during domestic altercations. So, while I agree that it's important to think critically about stigma and stereotypes, it's also important that we don't valorize these animals or the owners who raise them in a manner that compromises community well being.

oja16 — June 1, 2012

do you have a fb fanpage

matthew — December 17, 2012

I think one dimension that's not touched on in the picture or analysis is the issue of masculinity. How do animals reflect/symbolize what it means to be a "man" in a particular context?