Wing Young Huie and Doug Hartmann share two passions: playing pickup basketball and talking about race in America. So it seemed only natural, when they started to think creating about The Society Pages’ Changing Lenses project, to start there. Doug asked Wing to take a look at a book chapter he’d written on Michael Jordan and see what, from his extensive portfolio, sprang to mind.

The chapter came out of historian David Wiggins’ collection of biographical sketches of the most famous African American athletes of the 20th century. Doug says, “I didn’t have any new information or inside insights to contribute about Jordan’s life or career. Instead, I looked at the evolution of Jordan’s public image over the years of his career, focusing on representations and discussions of race.” He wrote about how Jordan’s admirers and handlers talked about how MJ transcended race, both as a basketball player and an advertising pitchman, but using media archives and historical records, Doug thought it was pretty clear that Jordan was always defined by his race. Even asserting that the reverence of Jordan rose above race only served to underscore the fact that he was black. To be fair, it wasn’t always negative; indeed, some of his legendary popularity (market research in the 1990s claimed the back of Jordan’s head was more recognizable to mall patrons than a photo of the President of the U.S.!) stemmed from the brand of blackness he represented and embodied. Ultimately, the piece turned into a case study of the paradoxical structuring force of blackness in post-Civil Rights America, and Doug has since given talks using these insights to make sense of other racial phenomena, including Barack Obama’s campaign for the Presidency.

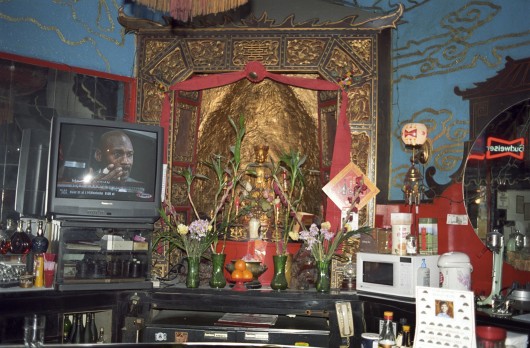

For his part, Wing quickly thought to this photograph from his Asian American/Ethnocentric Tour. “In the nine months I spent driving through 39 American states photographing the cultural landscape,” Wing recalls, “this scene as much as any reflects my own confusing, idiosyncratic hyphenated American experience. I am from Duluth, Minnesota, the youngest in my family and the only one not from China.” As he looked for Asian America, Wing says, “The closest you can get to anything resembling my Motherland is Chinatown, and the mother of all Chinatowns is in San Francisco (sorry, NYC!).” So it was “with peculiar pleasure” that Wing settled into a bar in this “faux-exotic destination” and watched Michael Jordan retire for the last time in what Doug calls “a semi-sacred, semi-profane context.” “Buddha was a foreign concept for me,” said Wing, “since I was weaned on Snoopy, Mary Tyler Moore, and the Vikings. I grew up Presbyterian.” But sport in America is a sort of secular religion.

Doug responds, “Athletes occupy a special place in our culture. They’re prominent social figures and cultural icons. Whether we’re considering race or masculinity or something else, we can learn a great deal by observing athletes, how regular folks view and talk about them, and how and when all of this happens”—even if it’s in a cozy bar’s confused shrine somewhere in just one niche of this vast country. Michael Jordan may not have transcended blackness, but seeing him in the unique context of Wing’s photo complicates and expands our visions of race and multiculturalism in an increasingly diverse America.

Comments 3

Letta Page — March 13, 2012

The thing that always strikes me about this picture is the larger-picture sacred/profane divide: what appears to be a Buddhist shrine (a Tibetan style one, no less!) in a bar! In Chinatown! Add in the TV and it's some hilarious brain-bending fun. It's funny to me that the idea of the idol worship stuff between MJ and Buddha seem to be the second layer of inquiry when I look at this image.

Kyle Green — March 13, 2012

Great first post. This really shows how well art and social theory can work together (something the art world and the social theory world tends to ignore).

I agree with Letta that the sacred/profane divide is immediately striking when viewing the photograph. I wonder how different our reaction would be if the picture was taken in an Irish bar and it was a cross next to television. Would we even find the sports star/christian iconography juxtaposition surprising?

There is also something perfect about the emotion expressed on Jordan's face. It gives the picture a much different feel than if it were a highlight of Jordan dunking the ball.

I look forward to seeing what this collaboration will bring in the future.

chris uggen — March 13, 2012

i love the collaboration here -- and find it really generous of Wing to share full-on scans of such powerful images. i hadn't realized that i could "click to embiggen" -- wow!